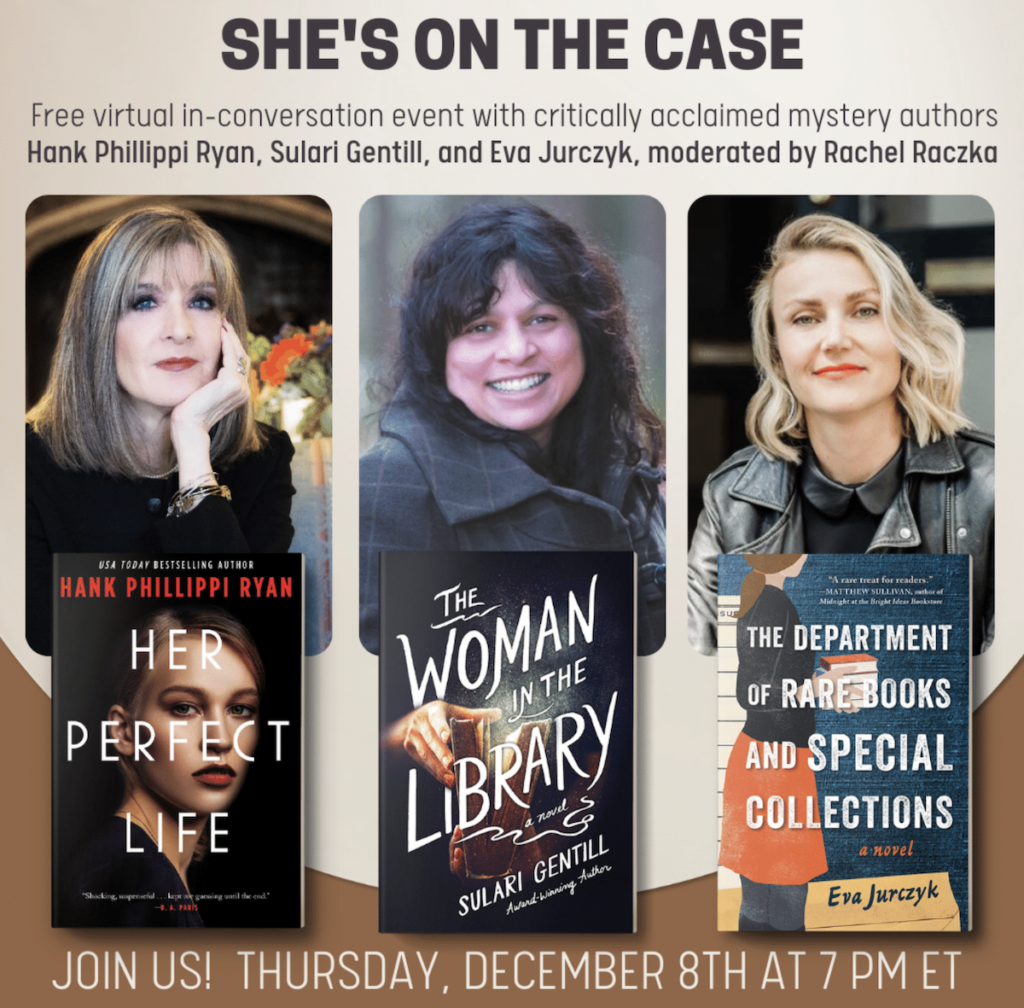

My annoyance, followed by curiosity, all began with the announcement of a panel of “acclaimed mystery authors” which I promoted in the December 1, 2022 Mystery Book Club “events” email. See below.

I thought, well, if I am promoting it, perhaps I should attend the online event. Then I thought, it might be best to read at least one of the author’s books so I could form my reaction based on what I read and not just whatever hype may be exuded during the panel.

I have read Hank Philippi Ryan and consider her books mediocre, despite her omnipresence at organized mystery book conferences. So not her book; that left the other two authors, each having written a mystery involving a library.

Going into this, my impression was that I would be choosing between two cozy mysteries featuring an amateur hero, probably the librarian.

Which “library mystery” would you choose to read?

The book blurb for The Woman in the Library by Sulari Gentill suggests that a good part of the story takes place at the Boston Public Library which definitely appealed to me. It also suggests that the key murder suspects are “four strangers who’d happened to sit at the same table, pass the time in conversation and friendships are struck. Each has his or her own reasons for being in the reading room that morning…” Hmm, a lot of dialog and not much plot? Meh. The blurb goes on to say the book is “an unexpectedly twisty literary adventure that examines the complicated nature of friendship….” Hmm, what does “literary adventure” mean? Sounds like an oxymoron to me.

Maybe Gentill’s book is more like an “unreliable narrator” thriller… without the thriller part. Okay – next choice!

The book blurb for The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections (hereafter, DRBSC) by Eva Jurczyk suggests multiple mysteries facing Liesl Weiss when she is suddenly thrust into the role of acting Director of the Rare Books Collection at a major Toronto university after her boss has a stroke: (1) The library’s most prized manuscript is missing. (2) Then a library staff worker goes missing as well. Hmm, this sounds more like a solid cozy that could interest me.

So I began reading DRBSC. First of all, it has a great opening line:

From the first spin of the lock, she knew she wouldn’t be able to open the safe. What does a librarian know about safecracking?

Okay, I keep reading. During the first three chapters, conflicts appear one after another: the blustery, sexist, male university president makes demands of the newly elevated female assistant director; an wealthy yet crass old donor wants privileged access to a rare document now (but it can’t be found); a professor from the math department demands to have a rare library document carbon-tested to establish its actual age (but will this destroy parts of the document?). Okay, the author has my attention.

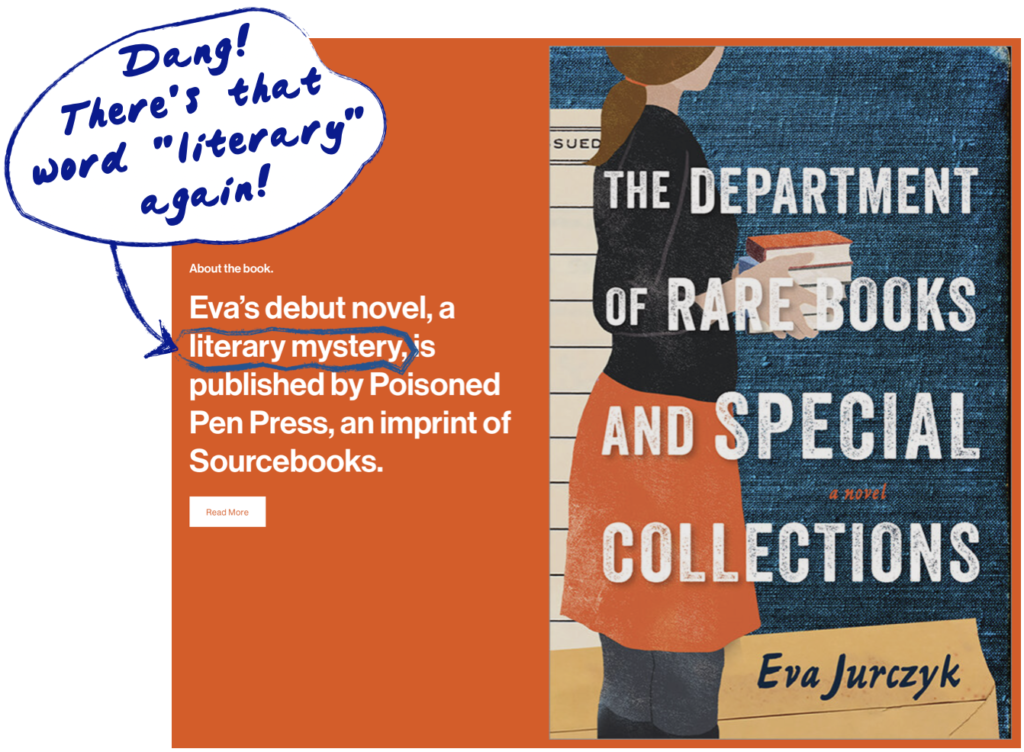

It was about that time that I decided to go to the author’s website to see what else she had written. Turns out, this is her debut novel. And on her website’s first page, I saw this:

Hmmpf. “Literary mystery.” Not being too sure what that meant, my guard was up. Maybe because it gave me the impression of a self-important author.

All in all, the plot was interesting enough to keep me reading, but it was buried in tons of conversational gibberish. The main character, Liesl, is not especially likable. She is wishy-washy: does she love her husband, or a colleague (now her subordinate), should she call the police about an apparently stolen rare book or not, should she stand up to the university president, her staff, and fussy donors– or not?

Jurczyk, like Liesl, is a librarian. And like her main character, she is highly critical of genre fiction using John Grisham as her scapegoat. As though the legal thriller genre is inferior to her “literary mystery” genre:

- Page 206: At a wooded crime scene, previous campers cared so little of Grisham that they used the paperback as kindling. “A fire pit contained the charred spine of a Grisham novel.”

- Page 224: Detective Yuan, confesses that rare books don’t interest him as much as a good mystery. “I’m more of a Grisham man myself,” he says, like an apology.

- Page 261: The university president, Garber, introduces Professor Langdon Sibley to Liesl as “the name I hear most when I ask about great libraries.” Does Sibley know Christopher Washington [the current Rare Books Director currently comatose from a stroke]? Sibley replies –

“Socially, of course. He once sent me a John Grisham paperback for my birthday. As a kind of joke.” Garber’s smile was so wide. He didn’t get the joke at all.

(261)

- Page 296: As the books from Washington’s home office were boxed for return to the university library, his wife …

Marie had stood in the office doorway and wept, issuing occasional instructions about how to pack a box full of books in a way that would not damage their bindings. When they were finished with Christopher’s office, all that remained on the shelves were a few hardback John Grisham novels that had been removed from their book jackets, probably so that no one would notice that they were John Grisham novels. If a man was defined by the contents of his bookshelves, then Christopher was nothing more than a few airplane books, trying to pass themselves off as something grander.

(296)

It is telling that Jurcyzk mentions only Grisham in these allusions to her idea of inferior writing. Is it the only best-selling mystery she has read? Does she have a personal grudge against him? Does she consider the unrealistic repetition of her opinion using Grisham to be a “literary symbol” of genre dreck? I consider it poorly done nonsense.

Back to the question: What the heck is a literary mystery?

Essentially, it is a perceived combination of a “literary novel” and “mystery genre book.” There are, in my judgement many sub-genres to the mystery or crime fiction genre. I’ll write more about that in another post. Here I am focused on the question of a literary novel or literary mystery.

Jane Friedman wrote an excellent article in which she cites Four Pillars of literary fiction. Well, it is excellent for getting the gist of what different experts think but also how muddy the waters can be. I am summarizing:

Pillar 1: It is an intellectual work; it is about ideas.

- “It has an overarching theme distinct from the narrative.” [Note 1]

- It “is more deeply thought provoking than genre work.” [Note 2]

- “While genre fiction (as a whole) seeks to distract the reader through light entertainment, literary fiction is much more introspective in its objective. Literary fiction as a whole wants to make sense of the world around us by exploring the human condition. [NOTE 3]

Pillar 2: It is has depth.

- Many books have sub-plots. But a book with depth interweaves the theme and ideas all through the plot and subplots. [Note 1] [Confused yet? First the theme must be distinct, now it must be woven through the narrative.]

- “Stories that explore the human condition aren’t exactly fun reads. By nature, they have to deal with a difficult subject matter with unflinching honesty. It can be a tad uncomfortable to think about these issues when you, as the reader, simply want to escape. Literary fiction may rely on symbolism or allegory to convey a deeper meaning. There’s almost always a deeper takeaway than the story itself reveals.” [Note 3]

- It “is always a study of the human condition and often an exploration of difficult social or political issues that control our lives. For this reason, it’s generally considered more “serious” than genre fiction.” [Note 4]

Pillar 3: It is has deeper characterization where the characters drive the plot.

- It “is focused more on character than plot.” [Note 2]

- “…The plot stems from the characters. The main character behaves in a particular way because that is who he or she is and it is their key character traits that drive the plot.” [Note 1]

- “Literary fiction doesn’t just show the characters in action, it also shows how every action changes the character.” [Note 3]

Pillar 4: The writing style is beautiful.

- It is the opposite of “workman-like” writing. “The prose can be more workman-like if plot is the driver. Take Stephanie Myers’ Twilight Saga. Supremely popular, these books do not fit into the literary fiction category. They do have interesting characters, they contain ideas (about the nature of vampires and vampire-human hybrids), they reference literature (Tennyson, Wuthering Heights, Romeo and Juliet), but they are predominantly plot-driven, the prose is on the workman-like side, the characters are not deep and the books lack depth. They’re still a great read.” [Note 1]

- Quality writing uses subtext, according to 55 Fathoms Publishing. “In more mainstream forms of creative writing, generally every line means exactly what it says. In subtext there are meanings that lie below the surface, revealed through subtle phrasing and nuance. Think about how people act and speak in real life. They almost never tell you what they are really thinking. They hide their personal agendas, and act in ways that they think you want to see. Literary writing captures that aspect of communication. It allows the characters to have hidden agendas and desires, and it reveals them in a subtle way, through what they say and what they do. We believe that creates a better illusion of reality than a mainstream story.” [Note 2]

- “Unlike, say, Thrillers or Science Fiction, Literary Fiction doesn’t follow a formula. A story arc may or may not be present, which also means that a satisfying ending is no guarantee. The line between hero and villain is often blurry, as is what they are trying to accomplish. And without a tidy plot to spell out every character’s motive, intangible details — metaphor, symbolism, or imagery, for example — play a larger role in telling the story.” [Note 4]

Conclusions

- Wildly: “Character-driven stories, social and political themes, irreverence for storytelling norms — these elements set Literary Fiction apart.” [Note 4]

- The definition of “literary fiction” changes over time. See Source 5 below.

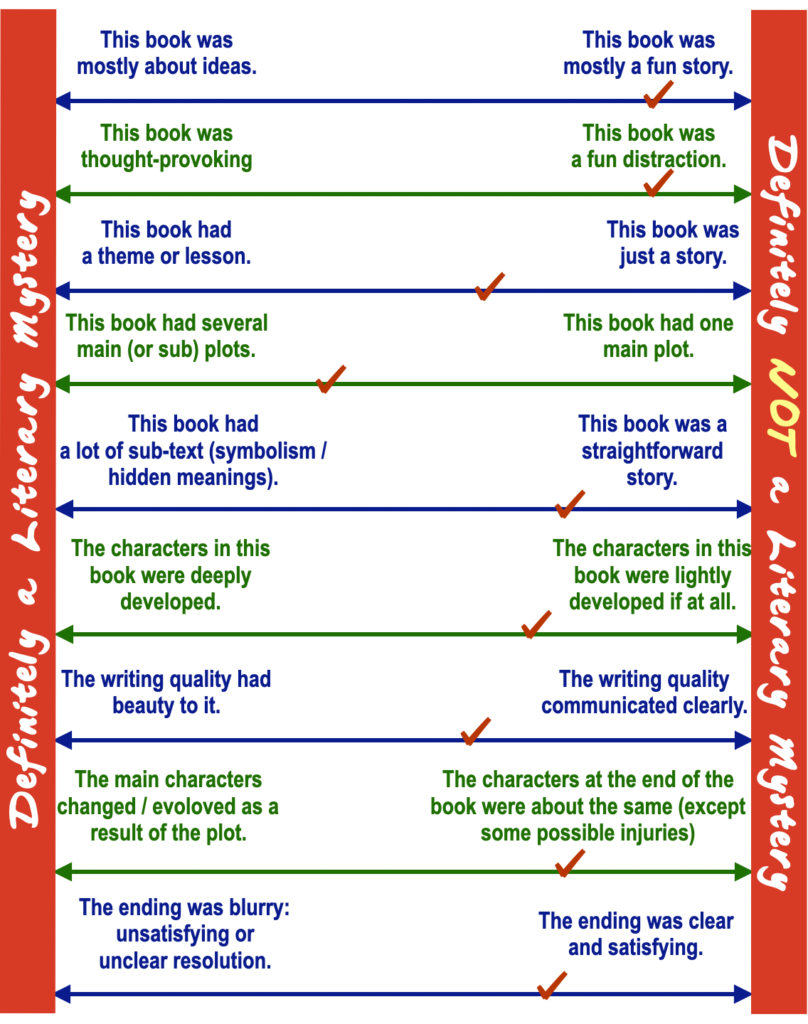

- Some limited number of crime fiction books can be clearly designated as a “literary mystery.” A large number of of crime fiction books that are well written and very entertaining can be confidently identified as “non-literary mysteries,” which is Okay! Many other crime fiction books seem to be somewhere in the middle. That’s where my sliding scales come in to help evaluate the book. (See my diagram below)

- All of the Four Pillars can be true of genre fiction, including most of the sub-genres of crime fiction. But think of the Four Pillars as sliding scales (my diagram below). The more you mark the scales to the left, the more likely someone will call it a “literary novel.” The more you mark the scales to the right, the more it will be considered genre fiction and the less likely this question will ever be considered: “Is this an example of literary crime fiction?”

- The example check marks show a book that is not a literary mystery but could easly be a very entertaining book!

Just remember this is largely a subjective evaluation, as you will see in the final section below where we suggest “lists of literary mysteries.”

And by the way, The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections does not score to the left of the evaluation diagram on hardly any of the continuums in my opinion. It is simply an average cozy that nevertheless does have a highly developed lead character.

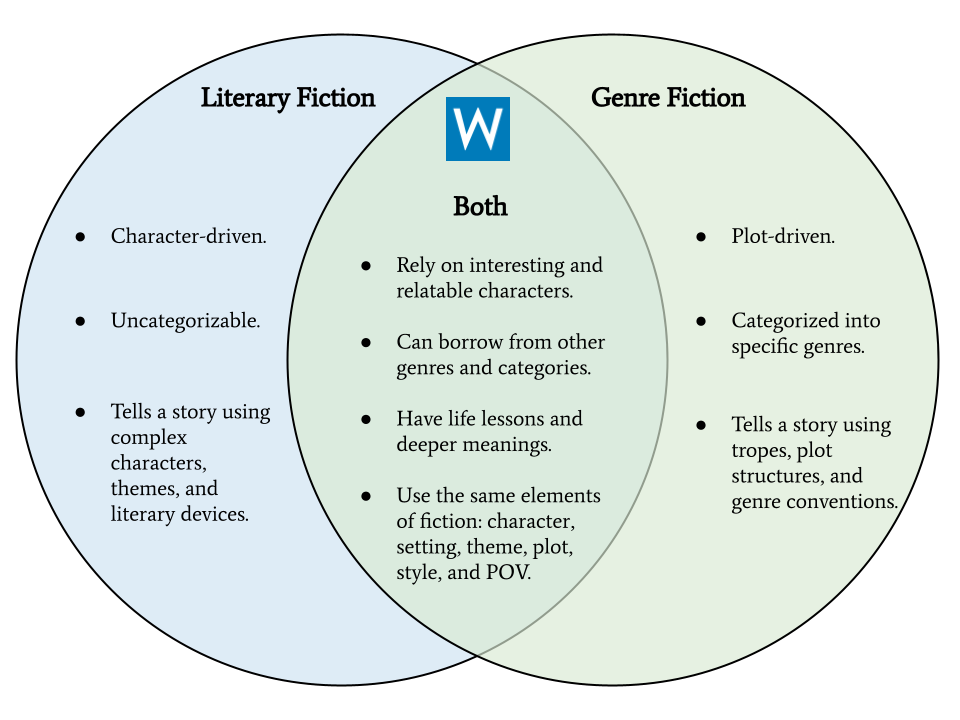

EDITED: Now I see that my continuums have literally reinvented the [two] wheels. See below. The diagram is from Writers.com – [Note 6 below.]

Sources by Note Number:

- https://www.janefriedman.com/what-is-a-literary-novel/

- https://55fathoms.com

- https://nybookeditors.com/2018/07/what-is-literary-fiction/

- https://celadonbooks.com/what-is-literary-fiction/

- https://www.newyorker.com/books/joshua-rothman/better-way-think-genre-debate

- https://writers.com/literary-fiction-vs-genre-fiction

What are examples of a literary mystery?

Here are a few literary mysteries commonly agreed and familiar to most.

- Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier

- The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

- The Distant Hours by Kate Morton

- In the Woods, by Tana French

- Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

- The Spy Who Came in from the Cold by John le Carre

Here are a few lists. Many of the books in any list would probably be vehemently contested by a lot of readers. No matter how objectively we try to define a “literary mystery” it remains a subjective matter.

- 15 propulsive literary mysteries that balance plot and prose By Anne Bogel

- 12 Mystery Novels for Fans of Literary Fiction – by Heather Bottoms

- 11 Literary Mysteries for the High Minded Sleuth – by Grace Felder